Punishments and Rewards don’t work, so don’t use them.

This is the 3rd part of my series of blogs on behaviour. I have promised to talk more about how I became a relational practitioner. And I will get to that, but first let’s deal with punishments and rewards, and why they do not work to effect any meaningful change in behaviour.

In my previous blog, here https://www.neuroteachers.com/post/a-controversial-blog-about-behaviour-part-2- confessions-of-a-recovering-behaviourist I talked about two year 8 pupils called Precious and John. Precious and John had found a lighter from somewhere and were burning the corner of one of the displays. I tried again with my assertive discipline voice

‘I want you to stop burning the display and give me the lighter.’

To which Precious replied ‘ No! It’s my lighter, get your own!’ and carried on burning until the fire alarm went off.

Setting fire to the school is a serious incident of challenging behaviour. For an explanation of challenging and disruptive behaviour see my video below. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t4BEpTUC04U

It could cause harm to both of the pupils involved, destruction of property and danger to other students and staff. There have to be consequences to such actions. I would never argue against consequences, but the punishment meted out on these two 12-year-old children did not encourage them to ‘learn how to behave’. Quite the opposite in fact. Later on in my previous blog I wrote; The impromptu fire drill ended with Precious, and John being taken to the

Head’s office and sent home for a fixed term exclusion (Which Precious had already told me, was what they wanted, because ‘School is boring’.)

Is exclusion effective as the ultimate sanction?

The children got exactly what they wanted. John never returned to school. His parents, who were Romani, and hadn’t been keen on him carrying on with education past Primary school anyway, decided to home school him. Pretty soon he was working with his dad and brothers.

Precious ended up having nearly a month off school. Her fixed term exclusion lasted 2 weeks, then her dad took her on holiday to Majorca for 2 weeks. He got a cheap deal, which, even with the fines, was much cheaper than going in the summer holidays. When she returned to school, Precious lasted about 3 weeks then lit up a cigarette and sat smoking it in the middle of a science laboratory during a test. She told the teacher it was because she was nervous. Nonetheless, she was given another week’s fixed term exclusion. This cycle of re admittance and exclusion continued for the rest of the year until she was eventually moved to a pupil referral unit.

When I bumped into her in the high street months later, she told me she preferred it there because teachers turned a blind eye to her cigarette breaks, and she didn’t have to wear uniform. She also told me she now had people she could talk to about her ‘anger’.

The context for Precious’s ‘troubled nature’ , as our Headteacher called it, was that she had been witness to her mother dying in a motorcycle accident when she was 4, from which neither she, nor her father had ever recovered. Although the Head acknowledged this, she did nothing to support this fragile little family, instead resorting to the ultimate sanction.

So, the moral of the story is exclusion, did not ‘work’ for these two, year 8 students. Instead, it led to them both becoming one step further along a path they were ultimately destined to walk down. We’ve all met children like Precious and John. We can all predict who they are when we first read our class lists, look at their addresses/ backgrounds, strengths and needs. We know who will swim and who will sink. Why are we still allowing it to happen? Why we are trying to punish children who are victim of circumstances?

What about other sanctions?

What about rewards?

In my early days of teaching, I went all out with stickers, stamps, postcards, and certificates. I had a ‘fabulous prize’ box in my classroom full of party bag treats which children could win. I’d put the quieter children in my form/year on ‘good behaviour report’ so their compliance would be recognised and celebrated I now know many of the neurodivergent children were masking. For more information about why this is an issue, please visit my blog here https://www.neuroteachers.com/post/it-s-like-her-shoes-don-t-fit-a-story-about-the-consequences-of-autistic-masking

About the same time as my epiphany about sanctions, I realised rewards don’t work for these children either. They either encourage masking/ compliance, both of which can be damaging, or they aren’t meaningful. If you haven’t had ‘good enough care’ you can’t/don’t care about why a reward is being given. You also must have enough self-esteem to believe that you are worthy of rewards and some experience that getting a reward is a good thing. Otherwise, the reward is pointless and giving it is a futile action.

What if the sanction is a reward and vice versa?

Relationships matter most

Which brings me neatly to relational practice. This may sound obvious, but without truly knowing the individual, and why they ‘behave’ in a certain way, you cannot expect to effect any meaningful change. Children, like all people need other people to help them regulate and get back into their window of tolerance (for more information, visit my blog here) https://www.neuroteachers.com/post/but-he-just-can-t-concentrate-ben-and-the-dust

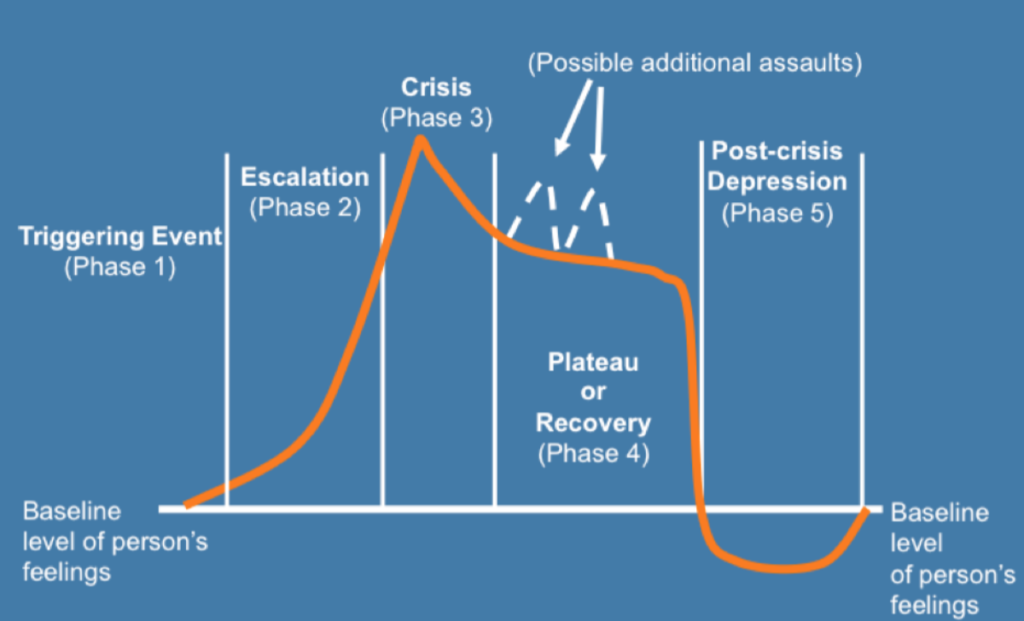

We are more likely to be able to move through our assault cycle (see below)

when we trust the person attempting to bring us into their calm, which is why relationships matter and relational practice works.